Decision Model Ethics

I recently finished a class, Ethics in Literature. In it, the focus was extreme cases—Frankenstein, Antigone, The Hunger Games. I wanted to understand how to take the ethical theories and apply them to life’s choices.

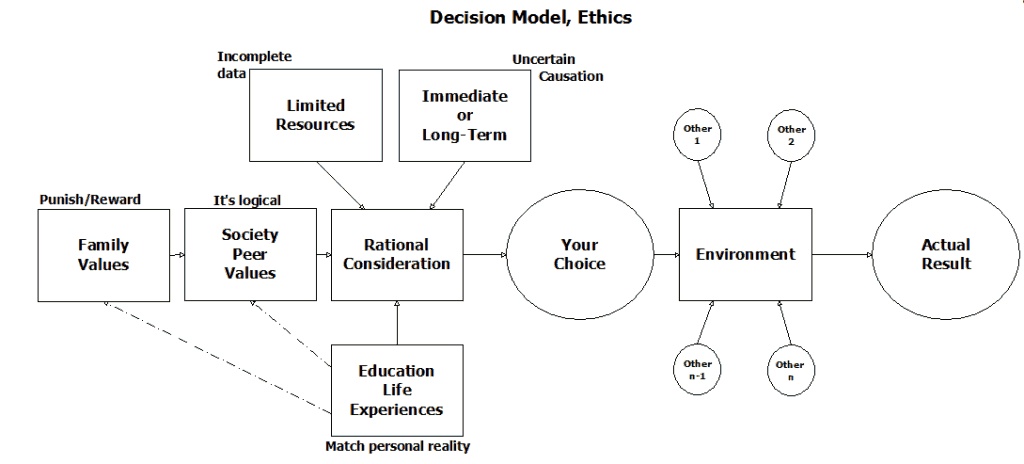

Here’s a decision model I came up with.

In ethics, the assumption is decisions are rational and situations certain. I disagree with both of those suppositions. The following thumbnail sketches of the boxes in the diagram above explain why I think non-rational elements play a large role in ethical decisions. Non-rational does not mean crazy or beyond sensible thought. Non-rational includes the peculiar incidents of your personal history that others don’t know. Those elements affect you before you learned to reason and continue to do so throughout your life.

Hierarchy of Decision Elements

- Family Values. Before the age of reason, you are told the good and bad of decisions. You obey because of punishment and reward.

- Society, Peer Values. When you develop reason (ages seven through twelve), you learn the logic of your society’s values. They may trump your family values, until you are under stress and revert.

- Rational Consideration. About thirteen, you achieve full reason. You can reason from your goals using your values to a path to get there. These may trump the prior value sets, unless you are not satisfied with the likely effect of your moral choice.

- Education Life Experiences. You decide whether your learned values fit your experience. You learn of other society’s solutions to life’s situations. You may adjust beliefs formed in early childhood under duress or in late childhood that don’t match your reality.

- Limited Resources. You only experience a sliver of reality, must accept much on authority, and have limited time, money, and effort to apply to any task.

- Immediate or Long-Term. You decide whether you want sure satisfaction now or possible greater satisfaction later.

- Your Choice. With all the preceding factors in action, you pick your action.

- Your choice now goes into the general world where other people are striving to achieve their desired actions. Sometimes their actions thwart your actions.

- Actual Result. Your result will often be different than your desired result.

Utilitarianism, maximum happiness for maximum number of persons focuses on the outcomes, but since the actual results are often different than planned, the maximum happiness is hard to know. Another shortcoming of that theory.

Kant argued that one’s intention is the sole way to decide the morality of a decision. Not considering the consequences goes against my grain.

Partial Information

The situations we are presented with upon which we must make decisions are not known with certainty to us. That person may have an unknown animus to us. Another may not even know we care about the outcome, yet can controvert our efforts without a glance.

If we allow our child to drive on Saturday night, their chances of car accident can only be lessened by sensible guidelines, but never eliminated.

The implication of partial and uncertain knowledge is discussed in Keyhole View of the World.

Our Moral Compass

We are animals with basic needs which lie deeper in our lives than rational decisions. These basic imperatives—satiety, sex, safety—get coated by personal, family, and societal perspectives which organize a unique set of individual experiences into one’s moral values. Those values are not fixed, but shift and adjust.