Daily Life over Epochs

Throughout human history, the daily lives of people have transformed significantly due to social, political, and technological changes. From the earliest farmer societies to the technologically advanced world of today, each era presents a unique snapshot of human existence. This essay will take you on a highlight journey through six distinct epochs, allowing insight into the change in social composition over the periods. By considering the daily lives of the preponderant number of individuals across these diverse eras, I aim to show the considerable progress society has made that has shaped human lifestyles. Join me as we traverse the sands of time, unraveling the rich improvement in human life won through the ages.

The Epochs

- The Agricultural Revolution, which began around 8,000 BCE, was a pivotal moment in human history as it marked the shift from hunter-gatherer societies to settled agricultural communities. This transition laid the foundation for the development of complex societies, enabling population growth, social stratification, and technological advancements.

- Classical Rome. The rate of change in daily life continued relatively slow, with most advancements occurring in the realms of agriculture, domestication of animals, and the creation of simple tools. However, as societies grew and became more complex, the rate of change accelerated. The invention of writing systems, metallurgy, and the wheel contributed to the development of trade networks, empires, and urban centers.

- Medieval Life. More than a millennium and a half later, a slow but steady increase in farm output allows the continued growth of non food producing workers. Religious occupations drive a significant portion of the supported by agricultural surplus.

- Industrialization. Merely two hundred years after the manor system started crumbling, agricultural surplus became available by trade to support factory workers who produced clothing faster and cheaper than cottage handmade products.

- Current Society. Nowadays, everyday life is marked by an exceptional level of interconnectivity, ease, and information accessibility, resulting in unparalleled worldwide interconnectivity and increased understanding of the varied experiences of individuals across the globe. More than two hundred years of technological advancements and industrial expansion have revolutionized the labor force. Only 2% of workers are employed in agriculture, while 25% are in industry, 65% in services, and 8% in unspecified occupations.

- Future. The rate of change in daily life has increased exponentially since the start of the Agricultural Revolution, with each subsequent era witnessing more rapid transformations than the last. This trend is expected to continue as technology continues to evolve and reshape human society in novel ways.

Daily Life in Ancient Days

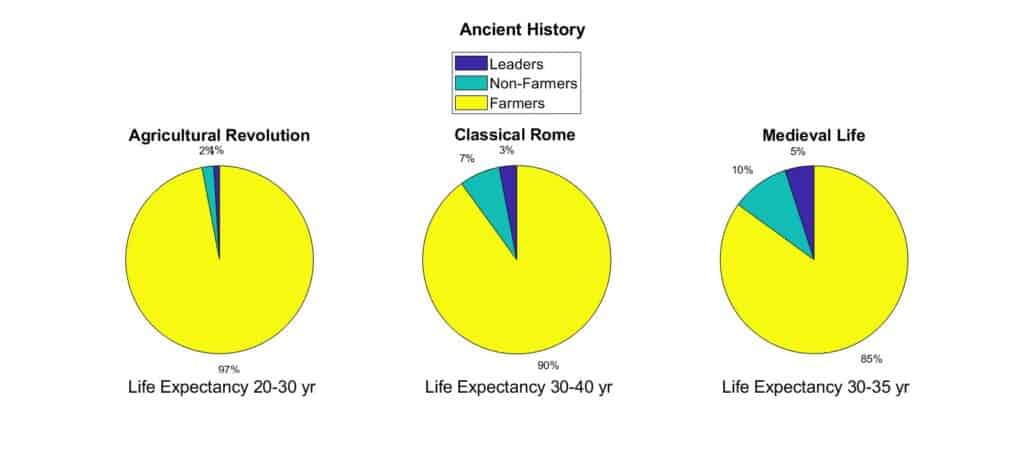

In the distant past, there were three primary groups that experienced daily life differently. These are the most accurate estimates of ancient population classes. One may quibble with the numbers and percentages, but the overall facts paint a consistent reality.

- Farmers lived a precarious existence, as their livelihoods were heavily influenced by the unpredictability of weather and seasonal changes.

- Leaders had a more comfortable lifestyle, with their needs being taken care of by others, while they made important decisions and resolved conflicts.

- Non-farmers, such as spiritual healers and tax collectors, played vital roles in the community by fulfilling specific duties and obligations. Their occupations offered a more diverse lifestyle than that of farmers.

From 8000 BCE to the conclusion of the Middle Ages, which encompasses 95% of human history, the figure below vividly illustrates in a striking yellow hue that the vast majority of people led their lives on farms, perpetually on the brink of starvation.

At the dawn of agriculture, almost the entire community worked on farms. There were a few rulers and a slightly larger number of assistants who could live off of the agricultural surplus. Average life expectancy ten thousand years ago was barely beyond early adulthood and parenting.

Gradual enhancements in agricultural practices reduced the need for farmers, freeing up a portion of the population to sustain an expanding ruling class and an even larger group of individuals who could dedicate their time and energy to non-agricultural pursuits, such as urban development, waging wars, and creating arts and books. A typical Roman citizen could expect living to see their children reach maturity.

One thousand five hundred years later, improvements in agriculture had increased the surplus allowing more members of society to devote themselves to other occupations, yet still 85% of all workers were farming. The life expectancy during the medieval era was strikingly similar to that of the Roman epoch, reflecting little improvement in overall living conditions.

Daily Life in Recent Centuries

Contemporary life stands in stark contrast to the days of the Middle Ages and earlier periods.

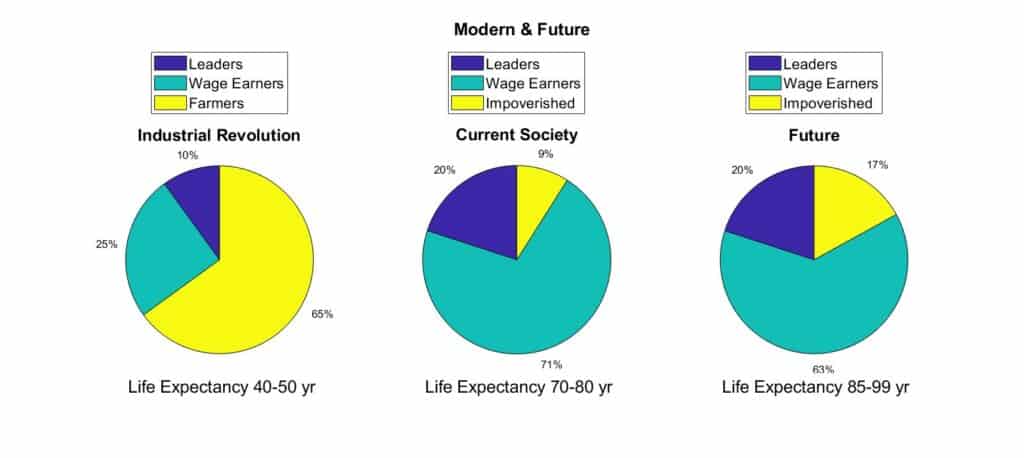

- In 1800, farmers are still the largest segment of workers, but the proportion decreases rapidly. The Industrial Revolution starts the rapid growth of factory workers and over the next two centuries, farmers shrink to about 2% of the workforce.

- Wage earners, that is, factory workers and the myriad jobs supporting town and city life, grown to become the dominant means that most of the population follow through their lives.

- Leaders as a group grew beyond the political and religious spheres to include economic and social decision-makers.

- The impoverished were more readily recognized as society morphed from subsistence farming to town life. Because of health issues or an inability to find and sustain employment, the impoverished cannot meet their basic living costs. Charities and eventually government programs came to help those who couldn’t earn enough to support themselves.

Please refer to the following figure for a visual representation of the changes in the proportions over two past epochs and our future epoch. I used Great Britain as the example of the Industrial Revolution and the United States for the current epoch.

The pie chart on the left, Industrial Revolution, shows the dramatic growth of wage earners and the corresponding decline in farmers and a 10-20 year increase in life expectancy since the sixteenth century.

A shift in attitude from self-sufficiency to specialization was triggered by Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. He introduced two important ideas that changed society: the division of labor and the invisible hand.

- The division of labor is the process by which complex tasks are broken down into simpler and more specialized ones, which can be performed by different workers with different skills and tools. Smith argued that this increases productivity, efficiency, and innovation, as well as the wealth and well-being of society.

- The invisible hand is a metaphor that describes how the self-interested actions of individuals in a free market are guided by an unseen force to produce outcomes that benefit the entirety of society.

The Industrial Age resulted in less expensive production of more goods, increasing the overall wealth of nations and the average wealth of its inhabitants.

The middle pie chart, Current Society, shows the consequences of two hundred years of technological advancements. It has led to the creation of new goods, such as electric lights, airplanes, television, computers, plastics, and more. The average worker today has a living standard that any ruler in prior epochs would envy.

The size of the leader class has grown as the vast increase in societal wealth supports more non-goods, non-food producing members. Farmers now are 2% of the workforce, so they no longer are broken out separately. The impoverished portion (9% in US) is composed of those who can’t work for health reasons and those who can’t hold jobs that support their lifestyle. Education, charity, and government welfare support aid but have not eliminated this group.

The improvement in life expectancy (an additional 20-30 years) since the start of the Industrial Revolution is because of factors such as improved medical care, better sanitation, and diet.

Every epoch has its own challenges. Current society must deal with obesity, waste management, pollution, and climate change. These tasks will require new jobs, societal changes, and the use of technology to address them. These issues and how we deal with them will affect the future.

The pie chart on the far right, Future, shows that although wealth will continue to increase, it’s likely that the impoverished class will grow because of a more unemployment resulting from robotics in industry and AI in services.

Life expectancy will continue to increase. Newborns today can expect to live in a society of 2120, which differs significantly from Current Society.

Implications for the Future

Soon, structural changes to occupations will accelerate. By 2027, according to the World Economic Foundation, nearly 70 million new jobs will be created worldwide and 83 million will be eliminated by automation. That makes up a reduction in employment of 14 million jobs, or 2% of the global workforce.

Many of the jobs being automated with robots and AI apps are routine, repetitive, and physically demanding. Those seeking the new jobs must show creative thinking, analytical thinking, and technological literacy.

Reflecting on past epochs, we have witnessed a remarkable transformation from a society where individuals toiled ceaselessly on the farm to one where most people earn enough to enjoy leisure time on evenings and weekends.

As we look towards the future, the rise of industrial robots and service AI is expected to render many jobs obsolete, similar to the loss of jobs in the agricultural sector, but that occurred over several centuries.

- As the 21st century progresses, workers in manufacturing and logistics (25% current workforce) can expect robots will perform a third of those jobs. A substantial portion of these displaced workers will need to undergo retraining, shifting from physically demanding roles to those requiring more conceptual skills. A Government Accounting Office study found that 44% of industrial workers who went through retraining were employed at a similar pay scale within two years of completing the training. Let’s use a 50% success rate. That means there will be a 4% increase in unemployment (1/3 of 25% current employment, rounds to 8% and with only half of the laid-off employees successfully retrained).

- In the services sector (65%), even more substitution is expected. By 2100, AI bots might take over a quarter of the front-line jobs in this sector. However, since the affected employees already have gained abstract skills, their retraining success rate may be higher. Let’s estimate two-thirds of the displaced workers get new comparable pay jobs. However, because of the large numbers of positions involved, this will cause a 5% rise in unemployment (1/4 of 65%, round to 15%, with one-third not successfully retrained).

Future

The pertinent question then arises: how will people who no longer have jobs earn a living? Who will be the consumers for the proliferation of goods and services produced by increasingly efficient manufacturing and service sectors?

If current trends continue and unemployment reaches 17% by 2100 with no intervention, nations around the world will face a wave of discontented citizens, posing a significant challenge to social stability.

A potential approach is a birthright certificate. Each citizen contributes to the society, whether through consumption, creation, or following the laws and not robbing others. Everyone has a stake in the future of society. Let’s give everyone a sliver of the nation’s GDP, generated by workers, robots, and AIs as national Birthright Certificate. Each citizen receives an annual dividend of one-hundredth of the GDP divided by the total population (currently in US about $700). The amount grows as the economy grows. It must be large enough to help pay bills, to encourage impoverished individuals that they have an ownership in society, yet too low to inhibit desire to work.

Label this concept as quixotic or socialism if you wish, but consider the potential consequences of inaction. Stealing to get buy. Riots and revolutions to forcibly change the societal structure that gives the unemployed not chance to take part in the wealth being created.

Additional Information

Class Warfare and Status Quo Defenders of existing privileges can always claim they are being attacked.

Status Quo and Political Inertia Change is always resisted .

Social Contract, Crime, and Lack of Opportunity Crime comes from lack of opportunity, not just personal defect.