Short Story Craft

Reading “Determined Friend” a short story I wrote about 15 years ago, I realized I had learned a few new techniques over the intervening years. Perhaps writing them down will help me incorporate them more easily in future stories.

Dramatic Elements

These few points keep me focused on why I am spending effort writing the short story. They also help winnow out extraneous threads that can slip in.

- Passion. What propels my desire to write the story?

- Theme. What I want the reader to take away from the story?

- Character flaw. Aspect of protagonist that makes the theme occur.

- Premise. What if a (flawed protagonist) sets out to (perform a task) in order to (achieve his greater goal) and discovers that he has to (surmount his flaw) to achieve success?

These are meant to provoke the story development and not as iron shackles. For instance, the character flaw can be relative to the plot obstacle rather than an absolute flaw.

After a draft, a revisit to the story premise often occurs.

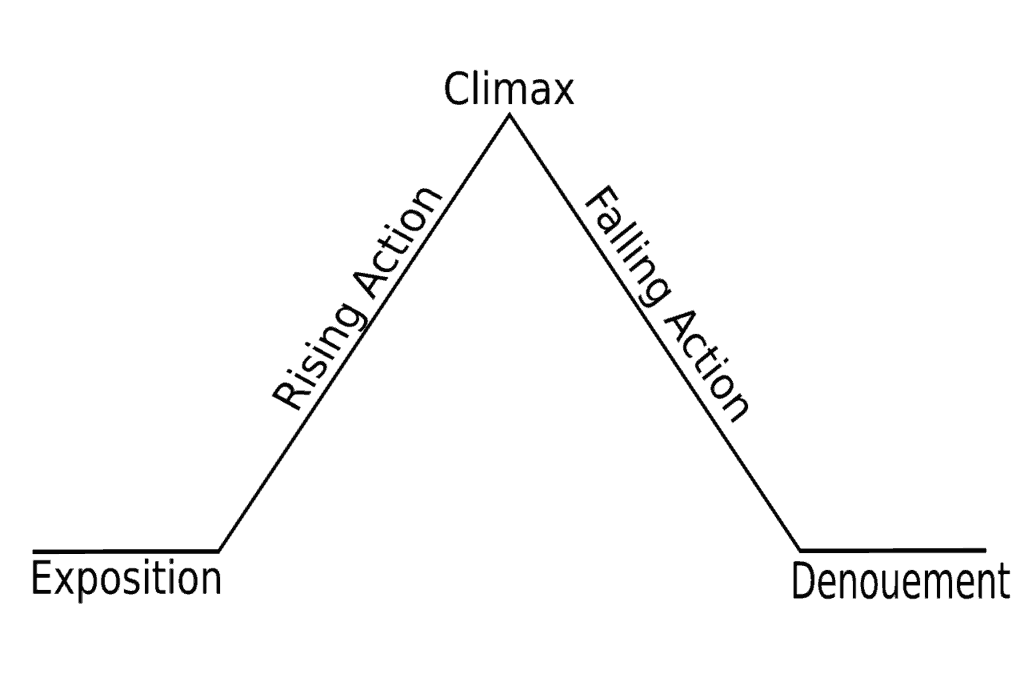

Three Acts. Nine Checkpoints

Writing the first draft is much smoother for me if I have general story ideas that I organize into three acts that cover the nine checkpoints, ensuring the story has depth, breadth, and completeness. Although this structure derives from film terminology, I’ve adopted for short stories.

Act 1. Intro into story. 15-20% of length.

- Hook. Exciting plot event (inciting incident) in which protagonist’s action hints at his flaw.

- Backstory. Can be several incidents, to show why protagonist is way that he is, esp. his flaw.

- Trigger. Scene. Intense event that protagonist must respond to (to achieve his goal and where he fails because of his flaw is an ideal story structure, often not achieved).

Act 2. Develop story. 50% of length

- Crisis. Sequel. Emotional, trigger’s effect on flaw.

- Struggle. Ever increasing obstacles to achieving goal.

- Epiphany. Character realizes flaw and overcomes. If character accepts his flaw, then story is a tragedy.

Act 3. Completion of story. 30-35% of length

- Plan. Using insight from epiphany.

- Climax. Confronts antagonist, who, ideally, is defeated by own flaw.

- Ending. Conflicts resolve with release of emotional tension.

Most stories satisfy some pieces of this structure and not others. That’s fine. The goal is to help organize the presentation of information to the reader. It eases the reader’s job of reading and understanding the story.

Immediate Scene

In the three act structure, some of the checkpoints (crisis and epiphany) are not necessarily scenes. They can be the result of quiet reaction to scenes by the protagonist. Yet however these insights are portrayed, it is important that the crisis is as clear to the reader as it is to the protagonist.

Nonetheless, most of the story will be scenes. There are two basic methods to portray action, by narrative summary and immediate scenes. Narrative summary implies that action is not described in detail, but a summary is given. This can done over extended periods as well as summarizing several minutes, like it’s written that the characters danced two songs without rest.

However, for scenes to truly reach the reader, the writer uses immediate scenes, particularly to write conflict scenes. Once the conflict is fully exposed, the writer returns to narrative summary to set up a subsequent scene of heightened conflict.

In an immediate scene, the flow of time is smooth, unbroken by gaps of minutes of unrevealed actions. It is the proper vehicle to show conflict between characters of opposing desires or goals.

There’s a functional structure that immediate scenes follow.

- Goal. Simple statement, in speech or thought, of what the protagonist is attempting to achieve.

- Value. Story value the lead character is entering with (hope, for instance), that at the end of most scenes will be reversed or altered in some fashion.

- Conflict. Typically 3-4 turns or twists in prospects for reaction the protagonist’s scene goal occur during interactions with others in scene, particularly the antagonist.

- Reversal climax. The last conflict in the scene thwarts the protagonist in some way, perhaps a definite No, but often Yes, but or in some cases No, and furthermore, where the furthermore leads to other complications.

All action is described in a single flowing experience via MiR units.

- MiR. Motivating stimulus. internal thought. Response

- Physical observable (M). The reader must see, or perhaps hear in dialogue, an action or provocation that the protagonist responds to.

- Internal thought (i). A little ‘i’ because it is only needed when the next physical reaction depends on the perspective of the character, which the reader may not share or already be aware of.

- Which prompts physical reaction (R). The reaction must visible to the reader, not just an irritation that the protagonist suppresses.

If reaction is not intuitively understandable, then brief internal thought (i) can mediate.

Naturally where the scene occurs in the plot will affect the way you shape the action and reversal climax. The final climax scene will rarely support a ‘Yes, but’ or ‘No, furthermore’ resolution. If that ambiguity is desired, often the ending is revealed by a ribbon twist, linking the final state back to an initial condition, thus giving the reader a verbal feeling of completion.