Decision in Ireland

| Upper Pasture | May 3, 1798 |

Patrick Hamill stepped his way down the path leading from the upper pastures of the Antrim Mountains. Patrick was a wiry, black-haired youth of 17. He was of medium height, now that his growth spurt had kicked in. He wasn’t solid like his Da or Hugh, his older brother. His muscles were lean and sinewy, but he’d always found them sufficient to any task he’d been called on to perform around the farm.

“Peatie,” he called back to his straggling brown sheepdog. “Come on. Hurry up and bring our little lamb down the path.” His Ma wanted something extra for the kettle of potato soup that she kept hot from spring to fall.

As Patrick walked down the mountain side, his mind wandered as it often did when there was nothing concrete to think about. He was fascinated by the stories of the Giants who had once roamed the glens and greens of Ireland. For his 14th birthday, Da took Patrick and Hugh to the fishing town of Bushmills. They stopped at ancient sites and to see family relatives along the way. They were gone for a week. One pleasant night in Armoy, they stayed with Ma’s brother Henry and his wife, Mary. At a party there, he first realized the charm of Colleen Magill.

The smell of salmon grilling and its taste was still with him, although it was three years ago. They caught more salmon in two days than they or Da’s family in Bushmills could eat. Even more than they could cart home. Patrick still remembered the pleased look on Ma’s face when they had given her, not only salmon from their rucksacks, but also the coins the excess salmon had brought.

They visited sites of the past that still burned brightly in his mind. The remains of Dunluce Castle made a delicious contrast to the Giants Causeway into the North Atlantic. Great men, like Sorley Boy MacDonnell, had expanded the castle beyond what God would stand, who took it back in a ferocious storm of the preceding century. It seemed that God would only let the Giants work last.

On their return they passed through the Armoy monastery where the round tower of human antiquity drew his imagination. Patrick wanted to go in through its door, more than six feet above the ground, pretending to escape from the marauding Vikings, but Da wanted to get home before the fish went bad.

Patrick took a large breath of the sweet Antrim Mountain air. He loved being in the open air. There was crispness in the May air of the upper pasture.

He saw Colleen Magill walking the lower path. He thought her a very pretty lass, her black hair a pleasing contrast to her pale skin with a sprinkle of freckles crossing the bridge of her nose. Colleen was a year younger than he. She was his cousin, a distant one, but wasn’t everyone a cousin since Adam and Eve? Their paths would meet at the stone fence marking the end of the open range.

She lived in Armoy but stayed often in Ballymena with her mother’s family. She usually stopped at the Hamill farm to rest on the trip to Ballymena. Although she was a year younger than Patrick, she knew more than he did. They had a school in Armoy and she was a good student.

Now, with Colleen in view, Patrick paid attention to his surroundings. No more daydreaming.

Pale blue flax topped thin stalks that rose to three feet on both sides of the path. Their abundance would assure that prices for flax and flaxen products would continue low in Ireland. His father and Hugh would have much work this winter but the pay would be small per piece. It had been this way as long as Patrick could remember, although his father told him that pay was twice as high in 1781 when Patrick had been born. There were no schools in Loughguile Parish,

their part of Antrim. Patrick’s mother told him that he had a good mind and learned things readily when he could rein in his imagination.

In not too long of a time, Colleen noticed him. She set something down and waved to him. They both hurried to the stone fence.

“Pleasant day to you, Patrick.” Colleen wore a comfortable walking dress, a bonnet that hid her fair skin from the sun, and a short jacket as protection against the wind and any rain that might bedevil her travels.

He smiled warmly. She was his favorite friend, although he saw her too infrequently. “And to you too, Colleen. Are you coming to our house?”

“Yes.” She glanced down to check her shoes. “I’ve been traveling since morning. The coachman let me off at Loughguile Castle. I’ve got a clutch of herbs for your Ma. Then I’m off to Ballymena as usual for the summer.”

“Let me carry something for you and let’s go to the house.”

She readily handed the herbs to him. “Thank you, Patrick Hamill,” she said.Then she ran passed him. “I’ll race you to the Little Giant’s Bed .”

| Encounter | May 3, 1798 |

They both caught their breath, hunched over the flat stone that balanced atop a three foot pedestal. “That was not fair,” Patrick finally was able to say, but his happy demeanor belied his words.

“Fleet a’ mind is better than fleet a’ foot,” Colleen taunted him. “Did I tell you,” she said turning the subject, “that I saw the real Carraigain last winter. Despite its name, little rock, it’s still twice as high as our little formation, taller than my Da, but it lacks the topping rock.”

“The Giant’s son with his little bed rests easier his father.”

They heard the clopping of approaching horses. In a couple of minutes four large horses carrying English soldiers came along the open field path.

“Peatie.” Patrick motioned for Peatie to get the little lamb off the path and behind the Little Giant’s Bed. Patrick and Colleen waited for the soldiers to pass, but the lead redcoat stopped his horse and the other soldiers followed his lead.

“I am Sergeant Bullock of his Majesty George the Third’s troops,” the large soldier said. “I demand to know what you are doing, Irish boy?” The redcoat looked at Patrick then quickly at Colleen and then beyond her, seeing Peatie and the lamb.

“I was up in the upper pasture.” Patrick usually offered no more information than necessary, but he couldn’t resist adding, “However I am not Irish.”

“You’re certainly not an Anglican!” The redcoat snorted disbelief that this young, poor farmer boy could be a member of the occupying class.

“No,” Patrick pulled himself fully erect. “I am a Scot.”

“I see.” Sergeant Bullock knew that he could treat this son of transplanted Scottish peasants as he wanted. “And what, young Scot, were you and the girl doing in the pasture?”

“She was not with me in the upper pasture.”

With a downturn of her lips, Colleen answered for herself. “I arrived on the coach at Loughguile this morning.”

Patrick continued, “We just met at the stone fence as I returned from tending animals.”

The English sergeant demanded. “And pray tell, does one small lamb rate being called animals?”

Patrick was glad he did not have the cows and sheep with him. “The rest remain ranging in the upper pasture.”

Sergeant Bullock mulled this over. With a smirk, he cagily asked, “Well my little Scottish boy, these animals, were they yours?”

Angered by the redcoat’s manner, Patrick abruptly answered, “No, they were not mine.” They were his parents.

“And yet you brought a lamb back with you.” The Englishman’s horse reared slightly and he looked down at Patrick. “Since you don’t own the animal, I will have to take it. I will make sure it is put to good use.”

“That’s not fair,” Patrick flared at the redcoat.

The large Englishman laughed and reared his horse. “Fair! You’re lucky I am not taking you in for stealing the animal. Hand it over and get out of my sight before I change my mind.”

Peatie barked at the redcoats as they galloped off with the lamb.

Colleen stroked Patrick’s arm. “It wasn’t your fault. The redcoats were wrong to take it.”

Although he knew that was true, he also knew if he had answered differently this might not have happened. “Come on. Let’s get to the farmhouse.”

| Rebellion | May 19, 1798 |

Patrick walked with his brother Hugh down the road to Fairhill where the Saturday market was held. The buying and selling of black cattle was the original reason for the fair’s charter in 1626, then butter and flax had been added. In the last decades yarn and linen had become important with a thousand pieces of 25 yards sold every week. More centrally located, the Ballymena Market at Fairhill was starting to draw people away from Portglenone’s market.

Hugh was taller, stockier, and more muscled than Patrick ever would be. He worked hard and constant in the fields during the season and tirelessly in the weaving shed during the winter. Although they had their differences of opinions, Patrick admired his brother’s steadfastness and sense of purpose. Ever since their oldest brother Roger had left the homestead for Dublin a few years ago, Patrick went to Hugh for advice, although lately he’d been just listening, not talking.

With a bark at a red deer, Peatie raced into the brush. After a short gambol, Peatie rushed back to Patrick’s feet. Unfortunately, the dog’s joyfulness on this pleasant spring afternoon escaped Patrick’s notice. The many greens of the Irish countryside were lost to Patrick. He was deep in conversation with his brother.

“Tone says,” Hugh explained, “that any man born in Ireland whether he is Catholic or Presbyterian or Anglican for that matter is Irish.”

Patrick, as every person in Ireland knew, that Theobald Wolfe Tone had founded the United Irishmen in 1791, but Patrick was only 10 at that time and still did not quite understand what the United Irishmen stood for. Although he was 17, he’d spent more time in fields and pastures than he had in learning what went on outside his little world.

Patrick wondered. “Yes, but what about Lord Clare? He was born here, but he certainly favors England, not Ireland.”

“That’s true. If you’re born here you don’t have to be a United Irishman.” Hugh shook his head. “I can’t explain everything to you. Oh, there’s the cloth of the linen tent.” He pointed to the dark green outline against the blue Irish sky.

Then Hugh picked up the thread of an earlier conversation he and Patrick had been having, “Yes, Patrick. Da will be mad at you for losing the lamb.”

Patrick nodded. He had no intention of telling Hugh or Da the curt answer that he’d given the redcoat and he hoped that Colleen would keep his secret.

The brothers walked down the main path passed the linen tent. The trading was completed there in the morning. Now the aroma of roasts and stews hurried the boys on. The crowd thickened when they neared the baking tents. From the flap of one tent, a voice rang out. “Patrick.” A broad smile came to his face when he saw Colleen’s black hair.

The brothers greeted her and found that their Ma was in the next cooking tent and their Da was at the ale tent. “Colleen,” Patrick asked the girl with the most education he knew, “why would Tone say that any man born in Ireland is Irish when Lord Clare hates Irishmen?”

Colleen shook her head. “What Tone meant is that any Irish-born man is eligible to be in the United Irishmen. Not that they all will choose to.”

“People like us, born here, Scottish and poor farmers, present company excluded, ” Hugh nodded to Colleen whose father ran a lime kiln in Armoy, “have more in common with Irish Catholics than with English Anglicans.”

“I agree,” Colleen said.

“Eligible?” Patrick asked, still mulling over Colleen’s words. “Just being born here is not enough?”

“Honestly, little brother,” Hugh said sharply, with the smugness of his extra years. “You must not listen to all that Ma and Da talk about.” He snorted. “Ma thinks you’re smart!”

“Eligible,” Colleen explained in a level voice but with a sidelong glance to Hugh, “means that any Irish-born man could join the United Irishmen if they agree with the principle that Ireland should be ruled by the Irish.”

“I see,” Patrick acknowledged Colleen’s explanation, but then turned to his brother. “But Hugh, there are big differences between Irish Catholics and Scottish Presbyterians. They can’t own land. We can. They can’t vote and we can.”

“There’s some truth and some lie in what you say,” Hugh said tartly. “It’s more complicated than that. Didn’t you know the Irish Parliament gave the Irish back the right to own land?”

“I don’t see any Irishmen buying new land,” Patrick said.

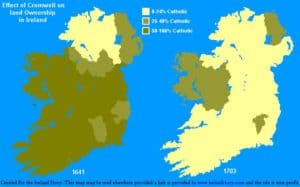

Colleen nodded then shook her head. “They weren’t given back the right to the lands Cromwell took. Now they can buy bad land with money they no longer have. It’s progress but mighty small.”

Hugh added, “And the land that we can own, Patrick, isn’t worth much.” Patrick knew that well. With Da, Ma, and two sons working their 30 acre farm, it was a very slow, uneven climb to success. Ma did extra piecework at home and Da and Hugh worked in the weaving shed many days during the winter. All to eke out a living.

Hugh continued, “the English Parliament can overrule whatever the Irish Parliament can vote in. Our vote is not worth much either.”

Hugh turned to Colleen. “We’re going into the ale tent. We will get Da to come out. You can come if you want.” Patrick grimaced. He wanted to tell his story without Colleen adding anything that might show his inadequacy in dealing with the redcoat, the insufferable Sgt. Bullock.

Their father came out with a tankard in his hand. “You boys finally got here. Did you get the chores done? Oh, and hello, Miss Magill.” He had been drinking a good while, Patrick could tell by the glazed look in his eyes.

“Da,” Patrick quickly and simply told of his redcoat encounter as soon as he could, ending with, “The English redcoats took the little lamb that I was bringing back to the farm.”

They were surprised when their father didn’t ask any questions, didn’t yell or even curse. He leaned forward and slurred his answer. “So the English took a lamb. It’s the smallest thing they’ve stolen from us in years.

“You boys are growing up and need to understand things. Yes, we are Presbyterians, but we are Irish now, not Scottish and certainly not English. We have been here for nearly 200 years, since Sir Hugh Montgomery came to the Ards Peninsula and granted this farm in Antrim to your namesake,” he nodded to Hugh.

“Thomas Emmet down in Dublin,” Da went on, “is planning a rebellion. Everybody but the ruling Anglicans are against the English rule. Your cousins, led by William Hamill, are planning for a revolt in Derry. Michael Dwyer has a large rebel army in the Wicklow Mountains, south of Belfast.”

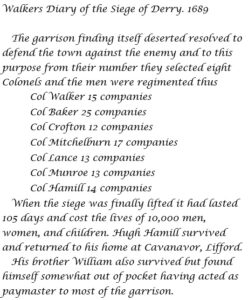

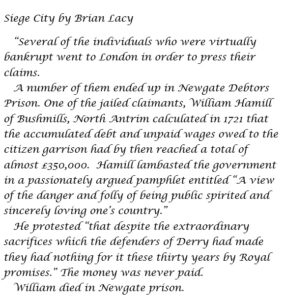

The Hamills of Bushmills had a role in Irish history as well as in the family’s history. Patrick recalled the story, first hearing it on his grandfather Roger’s knee. In Dec. 1688, when the Catholic armies of James II took siege of Derry, both Hugh and William Hamill had aided the besieged Protestants, whether they were Anglicans or Presbyterians.

Hugh Hamill was a colonel and led 14 of the 100 companies that resisted the Papists. William arranged for the financing of the defense of the city. When the siege was over, the English crown would not honor William’s expenses, even though it was on the Anglican’s behalf. The duty to serve the English King had died with William Hamill in 1721 in Newgate debtor’s prison.

Hugh’s eyes grew large. “We, Hamills, have always followed our passions and now mine drive me hard. The English must not continue to rule Ireland. We must have an uprising here too, in Ballymena!”

Across the fairway, Da saw Sgt. Bullock dismount his horse at the cooking tent.

Da turned to Hugh and tossed him three coins. “Such talk is best conducted in the privacy of the ale tent. Get you both an ale. Colleen can have an ade. I’ll meet you boys inside.” Da turned and reentered the tent.

Patrick turned to Colleen and then to Hugh. “I want to stay with Colleen. Tell Da I’ll walk back with you tonight.”

| Twilight | May 19, 1798 |

Colleen and Patrick took their drinks and settled in the thin shade of a lucky rowan tree. They rested quietly, alone with their thoughts, while the market visitors wandered between the tents.

When Colleen saw Sgt. Bullock brusquely gesture for the women to shut down the cooking tent, she was peeved. Yes, it was getting late and the ancient statute stipulated that the market should be closed by twilight, but the sun had just slipped below the houses. She asked Patrick. “What do you think Hugh will do? He was very adamant that the Irish must rule Ireland. And that the English should have no part in our governing.”

That was a question that Patrick had asked himself several times this late afternoon. He answered honestly. “I believe he will do something, but what it will be I cannot imagine. I agree with him that the English should be out of Irish affairs, but I see they are much stronger than we are and believe they can stay if they want.”

Her brow crossed. A noticeable line arose in her forehead. Although she was very attractive, Patrick knew that she was a strong woman, of firm opinions and not afraid to express them. “Will you help your brother and the other United Irishmen to throw off Sgt. Bullock and the English?”

He considered his answer carefully. He wanted Colleen to like and admire him, but he had to tell the truth. “I cannot see where and when Hugh will oppose the English. I will help him if I can, of course. However, I won’t fight a losing cause just to say I’ve fought. I do want freedom though. That’s very important to me.” He gained strength here. He was able to rework a favorite saying of his Ma. “As charity starts at home, so does freedom. I must be free so that my country can be free.”

They both felt comfortable enough in each other’s presence to leave the silence alone when it should be. When the red sun touched only the top of Slemish Mountain and evening was drawing in, Patrick started a new conversation. “In the upper pasture, in the early morning, I watched the ball of the sun come up, turning to see it lighting the mountains, reflecting off

the River Bann, and could sometimes catch a glimpse of Lough Neagh. It was quite beautiful. I saw the mists lifting off the lake being pushed by the Giant’s breath down the valley of the Bann until fogs formed at the base of the Antrim mountains. Tell me, Colleen, do philosophers of nature understand better than poets the whats and wherefores of nature?”

Patrick’s poetic musing brought a half-knowing, half-irritated smile to his companion’s fair features. “My teacher this year was not strong in science. The Day School for Ladies think it unseemly for us to know facts. I did get hints that natural philosophy in France has advanced despite the guillotine. Of course, the Germans are mastering their environment. Did you know that ships can go from the North Sea to the Baltic Sea through the Eider canal rather than around ? And we must give the devil its due, the English have made Isaac Newton’s theories the centerpiece of physical science.”

“It still amazes me,” Patrick said, only partly understanding Colleen, “that the apple falls because gravity pulls it and not because it’s seeking the center of creation, the center of the earth.”

She nodded and thought again how she often heard clearer ideas from her untutored friend and distant cousin than from her cultured school chums – not that she liked Patrick’s wariness about fighting for Irish freedom.

| Act Of Union | July 14, 1800 |

Patrick arrived with Colleen at the dark green canopy of the Fairhill ale tent. His Da was inside taking a pint with his friends, just as he had two years ago when Hugh had been with them. “I still can’t believe it. The Act of Union has become law. The Irish Parliament will give up its existence next January 1st. And Hugh’s still in gaol! “

The black-haired lass nodded her head sadly. “The Anglicans of Ireland chose security over freedom. They prefer to have their patrons in England rule them than risk any dilution of their powers by our weak Parliament. The few United Irishmen representatives were outvoted. And now Ireland will become part of the United Kingdom, as they call it. The London Parliament will find it even easier to trod over our Irish rights.”

Patrick nodded, having heard this since Pitt had gotten the vote he wanted. He tried harder now that he was the only son at home to keep up with the affairs of Ireland.

It was hard to accept that his brother was still in a Scottish gaol for stealing firearms. The United Irishmen had held the town for three days in ’98, sacking the Market House and holding it against the English . When they learned that the rest of Antrim had not risen up and that the English army was bound for Ballymena, most of the 2,000 rebels fled. Hugh Hamill had been one of the two hundred that had not.

Patrick had visited his older brother in Fort George Christmas Day when visitors were last allowed. Hugh wanted to know all the news. How were Ma and Da? Was there any word from Roger? What was the latest news of Thomas Emmet and the United Irishmen who escaped to Paris?

He told Hugh of the farm and that there was no news from Roger or the United Irishmen. He didn’t mention the confiscation of animals. The loss of the livestock was a terrible blow to the family’s fortune, but nothing could be done about it.

Patrick saddened as he remembered anew the sallow and gaunt look of his brother. Doubling his distress was that he could do nothing about it. Surprisingly Hugh tried to cheer Patrick up. He told Patrick not to worry about him, that he would be getting out soon and would leave for France, where the United Irishmen found a friendly reception.

His brother’s mature acceptance of his fate and the effort he made to ease Patrick’s concerns brought into high relief Hugh’s strong moral character. Patrick was envious again of his older brother’s strength.

Ironically, with Hugh in jail for standing up to the English, Patrick and Colleen were comfortable at the Saturday market at Fairhill. Despite the apparent joviality of the market, all around them was talk of betrayal and frustration and rage against the English overlords.

Everyone was in a fury at the impotent situation Ireland found itself in. There was anger about the duplicity of the Irish Parliament and the English crown. There was anger since 1650 that had never left with Cromwell’s departure. The English leader rampaged through Ireland, stealing the land from the Irish Catholics and granting it to absentee Anglican owners.

“Patrick,” Colleen gently recalled him from his reveries, “are you going to answer?”

Patrick shook his head to clear his mind. He really didn’t know what she had said. He started slowly, “The Act of Union means that there is no hope for Irish wishes to be honored.” That preamble would allow him to continue in any vein he wanted. “In London all they think of is their money and their Scottish landlords who are here. What is it that the Americans revolted against? Taxation without representation. That will apply here next January 1st.”

Colleen nodded with a dour smile. “And the French threw off their monarchy who abused them with excessive taxes and scant rights!”

“I certainly don’t want to see the guillotine used in Ireland,” Patrick said, “but we must have a way to live and prosper. What the English don’t tax, they take as fines – like when Hugh stood up for his rights. With only one cow, I don’t see how Ma and Da and the family can make it. And much less, how I’m going to set myself up!”

Colleen listened thoughtfully, then her face flushed. “Patrick, more battles would be fought and some will be lost before we win our freedom. Someone has to fight those battles.”

| Dublin | July 16, 1803 |

Patrick’s eyes gazed widely left and right, up and down. Dublin was by far the largest city he had ever seen. Although Ballymena might have two thousand people in it, during the November trade show, Dublin seemed to have that many people just near Trinity College.

He had come to the Irish capital because he had heard rumors of another uprising. The United Irishmen were planning in Dublin. Michael Dwyer, as always, led a band of rebels in the Wicklow Mountains.

There was not much he could do at the farm. Ma and Da lamented the fate of Hugh, their ‘heroic’ Hugh. Patrick felt deeply their unspoken disapproval of his inaction. That decided him. He had left for Dublin.

Colleen’s family sent her from Armoy to the Hamill household to escape the danger they felt was drawing near, but he ran into her at Trinity College in Dublin. She told Patrick, “I may be a woman, but I am an Irish woman. I will not avoid what will affect me most!” She left the countryside for Dublin and found a job doing cooking and light housework in the fine brick house of a Trinity professor.

Patrick had wandered the streets of the Liberties alone, searching the pubs and alehouses for revolution information. The ale flowed freely on Saturday July 16, 1803 in Dublin when his investigations finally drew out some information.

His drinking partner, a United Irishman, told Patrick that in August, Robert Emmet, Thomas’s younger brother, would lead them against the Castle in Dublin. Leaders in other cities across Ireland were ready to rise against the English troops when given the signal. France, having an opportunity to spite her enemy, promised to send a fleet to Lough Mayo with foot soldiers.

Patrick was excited and felt the importance of the coming events. As he drank the heady brew, his mind swirled. What would he do in the revolution? Would he be brave or foolhardy? Cowardly or instrumental in the rebellion’s outcome?

Those thoughts flew from his head when a huge explosion shook the pub that Saturday afternoon. All the men ran outside to see the cause. Down the street, a house was ripped apart. Fragments of its roof, floors, and sidewalls fell to the earth from the cloud of ash and smoke that obscured Patrick’s view.

Patrick’s companion whispered, “That’s where the bombs were being made.” The English would know that preparations were being made for an uprising.

Before any search could be made for survivors, before any of the debris could be removed, forces of the King arrived from the Castle.

“All right! All Right! You United Irishmen, stay where you are,” the officious Sgt. Bullock exclaimed. “I want to question you,” he said, pointing to a man across the street from Patrick.

Patrick quickly ducked into the closest doorway and ran the other way while Sgt. Bullock accosted the United Irishmen on the far side of the street.

| Goodbye Ireland | July 23, 1803 |

They stood quietly on the Custom House quay on the River Liffey.

“I can’t go.” she said with sadness in her voice. “Ireland is my home. I can’t believe you want to go, to leave Ireland.” The sunbonnet hid her fair skin from the strong sun of this July day. It was just seven days ago that the munitions had blown up in the Dublin house. “Don’t you want to help free Ireland?” She almost added ‘like your brother’, but she did not want to fight with him on what might be their last day together.

Patrick looked shyly down. “I don’t want to leave,” he swallowed hard, wanting to say what was in his heart, “but I must.” He too felt the finality of their conversation. He wanted to talk of them rather than Ireland, but that didn’t seem possible. “Colleen, I want Ireland to be free. I wish Ireland to be free, but I don’t believe it can happen. England is too strong. I must go where I can be free.”

She slowly nodded her head but tried a new tact. “Who will you talk to about the Little Giant? What about the stories of the past, our past? Who will you have to discuss them with?”

“That I can’t answer and I will miss it greatly until I can,” he admitted. “However I must be free. If I work hard and well, I want to prosper. Here, that’s just not possible.”

“Then this is goodbye, my dear friend. I wish you the best, but I cannot share your path.” She kissed his cheek and tasted the salt of his tears.

They hugged each other tightly for a couple of minutes, until the ship’s bell sounded.

As he turned and walked to the ship that would take him to America, he tried to explain himself one last time to her. “Colleen, I admire what Hugh did or tried to do, but that is not my way. I am not my brother. I must be free to be of use to myself and to God. I would be in gaol within a week if I stay here.”

As he backed towards the ship, Colleen murmured to herself, “I see now. I’m fated to stay behind. The right path for one person might not be the right path for another. Farewell, Patrick Hamill.”